Published: 23.12.2019

In 1989, Jiří Málek was 30 years old and went to Spain on a research stay. Therefore, he could only follow the 1989 events from abroad. He learnt from the press what was going on not only in Czechoslovakia. “No one knew what the outcome would be. But I would rely on young people even today,” says Jiří Málek, the Rector of the University of Pardubice.

Can you recall what you were actually doing on Friday 17 November?

Quite exactly. As a researcher at the Institute of Chemical Technology in Pardubice, I was doing a year-long postdoctoral fellowship in Spain at the Faculty of Chemistry of the University of Seville. Neither my wife nor my daughter could join me there. I followed quite carefully what was going on in Czechoslovakia. By that time, I had mastered Spanish well enough to read the Spanish papers, listen to the radio and watch TV. I cut some of the articles and I still keep these newspaper clippings, which offer an interesting insight into how the situation was perceived from the other side of the Iron Curtain.

How then?

The situation in Central Europe was discussed in quite a few articles. Sometimes, the events in Czechoslovakia even featured on the front pages of newspapers such as EL PAÍS or ABC. They published not only reports, but Saturday supplements also contained well-written political commentaries. That was something I did not know from Czech papers, except for the Prague Spring. Spain was very free at that time, and it seemed to me that the people, not only at the universities, were enjoying the freedom they had. In 1989 only 22 years had passed since the announcement of the first democratic elections in Spain, which marked the end of the transition from dictatorship to democracy.

Did you have any news from your family?

We phoned each other with my wife quite often, and my wife kept informing me of what was going on in Czechoslovakia. However, the Spanish papers did not only deal with the situation in Czechoslovakia, but also with the events in Poland or Romania, so I could tell her what was going on there. As Pavel Tigrid, a dissident and former Minister of Culture, used to say, in Czechoslovakia there was “a caravan of the stubborn”. The representatives of the regime resisted any changes. I was wondering what would happen. Even before the brutal intervention of security forces in Prague it was clear that the situation had started to change. However, the media were controlled by the communist party, and the journalists tried to relativize the events. If Prague did not receive support from other regions, and theatres and universities did not get involved, the situation may have developed quite differently. I am sorry, even today, for not living this historic event in Czechoslovakia.

Did you think of coming back?

That would be impossible, I could not just leave. The original plan was that I would leave in September, but I managed to extend the stay in spring until the end of the year. As much thrilled as I was, I had to follow the situation from abroad. I am currently working on my autobiography where I also describe how I perceived the revolutionary situation at that time. And it even affected my work.

In what way?

I was supposed to submit a paper to a journal, but you will understand that I could not concentrate on that. Then I saw the enormous demonstration in the papers, the Melantrich balcony which served as a tribune for speakers, and thousands of people below in the Wenceslas Square. I had an intuition that something “would collapse”. I hoped it would be successful.

One more question about your stay in Spain: did you face any difficulties travelling abroad?

I was extremely lucky; I had finished the then equivalent of PhD and started to work. Naturally, I wanted to do a post-doc stay abroad to gain experience. In the end I got an invitation from the Spanish government and was offered a scholarship that was personal and could not be assigned to another person. From October 1988 I was supposed to start an internship at the University of Seville and work in the research team of Professor J.M. Criado. However, had it not been for the support of the then rector, Professor Jiří Klikorka, I would have been hardly able to travel abroad.

After you came back, did you experience any changes?

Of course, I was in touch with my colleagues even from abroad. But let’s not forget that it was much more difficult than it is today; there was no internet or e-mail, and snail mail was slow, impractical and rather expensive. Right after my arrival, I joined all the activities. I was a member of the first Academic Senate; I could follow how the Institute of Chemical Technology was transformed into a university with more than one faculty.

Was the society ready for changes in the political system?

The society can never be ready enough. Not for such big changes. The people behind the revolution were ready in their minds. They could see what needed to be removed to make changes in the society possible. Thanks to the revolution, we joined civilized nations. And we should be grateful for that.

Do you think that today’s students would be able to show the same degree of resistance as university students back then?

I have trust in young people. I think it is no good to say that everything was different when we were young or that today’s generation is not reliable. Even today, I would rather believe in young people than in conformists who are dependent on many things and have various commitments. The students played a big role in the whole revolution. Had it not been for the students, there would have been no Velvet Revolution, not to mention such a successful end. Therefore, we are trying to prepare strike journals written by our students in 1989 for publication. They could see who the provocateurs were, they acted in a reasonable and correct manner. It is only logical that their activities were a few days delayed compared to the capital.

In your opinion, what was the biggest change brought by the revolution?

We regained freedom. I have been wondering which of the demands formulated by the students was the key one. There were seven of them, but I think the key one was the fourth one. The students demanded that the reference to the leading role of the communist party be deleted from the Constitution. Each totalitarian regime tries to get monopoly of the power and get as much power as possible in its hands. And the people behind the Velvet Revolution could see this. And this opened the road to free elections and democracy.

However, democracy means different things for different people...

But even democracy needs some fixed rules, which is often ignored. Freedom and choice are important. However, that involves rather a demanding decision-making process, which may have different outcomes. The success of some parties may surprise us, but it makes sense to keep fighting. It makes sense to go to the polls again and try to change things. Thanks to the freedom, not only young people can travel. I always advise our students to travel when they can. To take advantage of exchange stays and go abroad to enhance their knowledge not only about the subject matter but also about the culture.

Do you see the 1989 students as heroes?

Of course I do. They did not fear big changes and could formulate their demands at a time when it was by no means clear how the situation would develop. The older generation did not strive for a change, having the experience of the Prague Spring, which was followed by normalization and many people being fired. Many could not study what they wanted and the “sins against the regime” were taken as hereditary ones. That is why older people were more hesitant. And that is precisely why students and their courage was so important. I deeply appreciate all they did, and I am happy that they commemorate the events of 1989 with us today. Moreover, I am happy that such a change occurred in my lifetime.

Is there any point in organizing demonstrations such as the one at Letná or the Wenceslas Square in Prague?

I believe that if people meet voluntarily and express their views, it should not be ignored. Politicians should take that into account and listen to people. That is the essence of democracy. I do not like looking down on people. The politicians who are targeted at such demonstrations should at least consider that they may be doing something wrong.

Prof. Ing. Jiří Málek, DrSc.

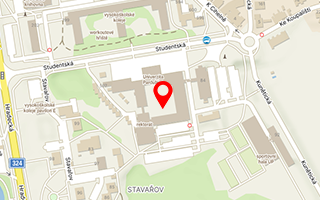

Jiří Málek graduated from Inorganic Chemistry at the then Institute of Chemical Technology in Pardubice (now part of the University of Pardubice), and later worked at the Joint Laboratory of Solid State Chemistry of the Pardubice Institute of Chemical Technology and the Academy of Sciences. He was appointed associate professor in 1997; in 2000 he was awarded the degree of the doctor of chemical sciences (DrSc) to be appointed professor in the field of Physical Chemistry only two years later. His academic history includes long-term research and teaching stays abroad including Universidad Hispalense in Seville, Spain, Universitat Politécnica de Catalunya in Barcelona and the National Institute for Material Science in Tsukuba, Japan. Jiří Málek’s research interests include kinetics in non-crystalline materials and highly supercooled glass-forming liquids. He conducted many research projects and co-organized many important international conferences. He authored or co-authored more than 200 research papers in prestigious international journals and monographs with more than 6000 citations. In the past he has held the office of the Vice-Rector for Development, Research, or International Relations. He took the office of the Rector of the University of Pardubice from 2006 to 2010. He is married and has two daughters. His hobbies include reading, travelling and photography.